For hundreds of years, Southeast Asia has held a sense of wonder for Western explorers. As late as the nineteenth century, there were still adventurers searching for uncontacted regions to discover. Today, backpackers, in their own way, are still seeking out those places. Traded like secrets in hostels, travelers gossip about those rare, hidden locations untouched by mass tourism.

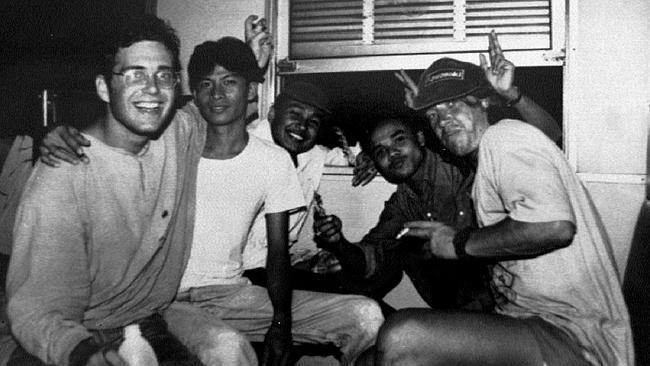

In the mid-nineties, Sihanoukville was one of those places—pristine beaches, legal marijuana, and accessible only to those with a sense of adventure. In July 1994, three backpackers in their late twenties—David Wilson, Mark Slater, and Jean-Michel Braquet from Australia, England, and France respectively—were staying at The Capitol Guesthouse in Phnom Penh when they made the decision to visit Sihanoukville.

Cambodia was a different place back then. Lonely Planet had only just released it’s first edition on Cambodia in 1992. The United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) had left the country in September 1993. Though Siem Reap and Phnom Penh had recently become regular stops on the Banana Pancake Trail, much of Cambodia remained off limits. Most embassies had issued advisories to avoid leaving urban areas. Outside of the cities there was a risk of violence from both the Khmer Rouge and other bandits. Kidnappings of foreigners—both tourists and NGO workers—were a regular occurrence.

Only a few weeks before, three expats had been kidnapped by the Khmer Rouge along the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville highway. The search for them was still ongoing when Mark, David and Jean-Michel were making their decision. While a taxi along highway 4 was the most direct way to get there, they instead chose to take the train, which wound through the countryside and passed through Kampot Province.

The Khmer Rouge had controlled large portions of Kampot Province since 1972. Both the Vietnamese and, later, the United Nations had failed to remove them. By the 1990s, an uneasy truce was in place. Vast areas of the province’s mountainous regions—particularly along the Phnom Voar mountain range, just north of Kep and west of Kampong Trach, as well as the Elephant Mountains—remained outside of government control and were administered by the rebels. At the time, Phnom Voar was one of the largest Khmer Rouge stronghold after the Dangrek Mountains on the Thai border, from where Pol Pot still ruled.

Cambodian trains were also different back then. They were equipped with machine gun nests and pushed several flatbed carriages ahead of them to detonate mines that bandits would place on the tracks.

On July 26th, as the train carrying the three backpackers departed Kampong Trach, it passed through a valley near Phnom Voar on its way to Kampot. That day, around 2 p.m., the Khmer Rouge were in the hills with machine guns and B-40 rockets, having planted two mines on the tracks. Rumors later suggested they may have been tipped off by spies working at the Kampong Trach train station that the train that day would be an inviting opportunity.

The attack itself wasn’t unusual. Over the past year and a half, there had been eighteen similar attacks on the route between Phnom Penh and Sihanookville, six of them along that same stretch of track through the valley. The train’s chief engineer would later describe it as ‘an average attack.’

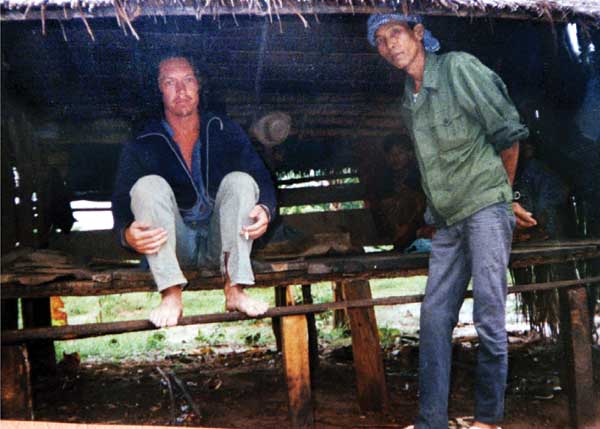

During the fighting, around a dozen people were killed and two dozen more injured. Once the battle was over, the rebels had a lunch from the plundered food, and then they loaded their loot into wooden carts and took roughly 200 hostages with them back to their base. Most of the hostages were later released, but they kept the Westerners, three ethnic Vietnamese, and several Khmer whose identity they couldn’t confirm. The Cambodians were eventually ransomed back to their families for a few hundred dollars each. The backpackers and Vietnamese were taken to a remote village under Khmer Rouge control near the mountains.

A trilateral team from Australia, France, and the UK, including several experts experienced in hostage negotiations, was sent to Kampot. However, being in a foreign country, they had no real authority to direct the Cambodian government’s actions.

Less than a year earlier, Cambodia had completed its elections under the United Nations Transitional Authority, resulting in a new government—a complex power-sharing arrangement where Prince Ranariddh and Hun Sen served as co-prime ministers. As reporters flocked to Kampot, the story became an international incident and a major crisis for the new government.

Adding to the complexity, the Cambodian military and government often operated independently, with the military often exercising a great deal of independence in their decisions.

The first news regarding the Western hostages came three days later when a woodcutter noticed some barang working in rice fields near Phnom Voar. He was approached by the Khmer Rouge, who handed him a three-page handwritten letter from Mark Slater. In the letter, Mark informed them that the Khmer Rouge were demanding $50,000 in gold for each hostage, assured that they were in good health, and included a photo.

A few days later, one of the train guards who had been taken prisoner was released. ‘I told them I was an ordinary person. If I had told them I was a train guard, they would have killed me”’ he said in an interview with journalists. “Every day we were forced to work. Hard labour. Like Pol Pot times”.

Five days after the kidnapping, another letter was received, this time signed by Noun Paet, the political commander of the Khmer Rouge forces in Phnom Voar. The letter reiterated the $50,000 ransom demand and threatened, ‘If it takes [too] long, I will send them to the Thai border,’ a Khmer Rouge euphemism for execution.

Prince Sihanouk reached out to Khieu Samphan, the nominal Khmer Rouge leader, requesting the release of the prisoners. Khieu responded by stating that the NADK (The National Army of Democratic Kampuchea, the armed forces of the Party of Democratic Kampuchea, the official name of the Khmer Rouge) had no involvement in the kidnapping, asserting, ‘We have never been involved in kidnapping foreigners for any purpose.’

The Western governments all insisted the ransom couldn’t be paid; it would lead to more kidnappings. They also rejected the idea that military action should be involved. However, with no single official leading the negotiations and the families desperate to have their sons back, it seems a number of negotiations took place. First through the Cambodian government, going against the Western diplomat’s request. An Australian businessman offered to pay the ransom himself. Several different Cambodians claiming to have contacts with the rebels also offered to act as intermediaries, however they would be taking a cut for themselves.

Further complicating the situation were the foreign reporters in Kampot who were desperate for stories. It had created a market for selling information and material; letters, pictures and other messages. While the hostage were being kept in an village controlled by the Khmer Rouge, locals who were friendly with rebels were able to contact them. At one point there were at least six different people being used as intermediaries, none of them officially. There were moments when it looked like the ransom demand was going to be met, only to have it fall though.

Despite promises from the Cambodian government, the military began shelling areas around the Khmer Rouge stronghold in an effort to hasten negotiations or drive them out. The Khmer Rouge, instead, increased their demands. On August 8th, they asked for $900,000 in “compensation”, along with watches and medicine.

By this time, the Khmer Rouge leadership recognized that the press coverage of the incident provided them with a powerful political tool. Although the UN had legitimized the Khmer Rouge as a political group, the new Cambodian government had reclassified them as an outlaw organization just a month earlier. Initially denying involvement in the kidnapping, Khieu Samphan now aimed to use the international press for propaganda. On August 16th, the Khmer Rouge added the removal of all military aid from England, France, and Australia to Cambodia as a condition for the hostages’ release. Three days later, they also demanded the withdrawal of the Cambodian army from Kampot Province.

As the situation intensified, the press became bolder in getting their stories. On August 19th, London’s Sunday Times published an interview with the hostages conducted over the radio. On the 29th, Reuters managed to smuggle in a video camera and recorded a half-hour interview in which the captives pleaded with the government to stop the shelling.

Frustrated with the media circus disrupting the negotiations, the Cambodian government declared an exclusion zone in Kampot Province, ordering all media and foreign diplomats to leave. General Chea Dara, the chief negotiator for the Cambodian government, was relieved of his position, and efforts to pay the ransom came to an end.

It seemed that even Khmer Rouge commander Noun Praet, who held the prisoners and was leading the negotiations, was frustrated with the amount of information getting out. In early September, he took steps to prevent people from visiting the hostages.

It was to be the last time anyone would hear from the backpackers.